An Exploration of Zigzagging

Dr. Brian McCue, Center for Naval Analyses

Download PowerPoint presentation

Download Excel Model

Dr.

McCue reminded us that “If you watch enough WWII movies you'll

be familiar with it, but I'll show you a couple things about zigzagging

that you don't get to see often.” Because we can zigzag into the

bad guys, as well as away from them, a common expression is: “This

better be worth it or we don't want to do it!” Dr.

McCue reminded us that “If you watch enough WWII movies you'll

be familiar with it, but I'll show you a couple things about zigzagging

that you don't get to see often.” Because we can zigzag into the

bad guys, as well as away from them, a common expression is: “This

better be worth it or we don't want to do it!”

Brian's examination of zigzagging used simulation modeling as a

primary tool.

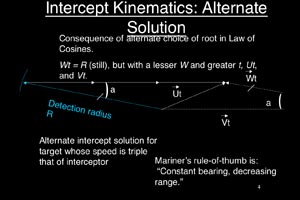

Brian discussed Intercept Kinematics as in the case of

a fast target being detected by a slow interceptor, and the target

doesn't have the ability to counter-detect the interceptor. He also

described this as the reluctant pirate interception course.

The capture section of the intercept is an important degenerate

case.

See enlargement

Zigzagging is done for various reasons. Mostly, the target wants to dodge around in order to spoil the interceptor.

The target might zigzag to get into a space where an interceptor

can't get to the target. A ship avoids torpedoes by zigzagging around

for hours.

In 1940, 44 pre-determined patterns were devised and course changes

were recorded for various threat levels. Admiralty Pattern # 16

was highlighted as an example for general use in submarine areas.

Zigzagging went unanalyzed however. Thomas Edison did some operations

research during WWI and gave up on it. The same thing happened in

WWII. The benefits were acknowledged, but so were the costs. Today,

with the advent of faster computers, explicit modeling can be accomplished

and zigzagging can be studied in greater detail and variety. Dr.

McCue modeled Admiralty Plan #16 as a computer simulation, and the

results were qualitatively similar to the original findings.

In the first version of the simulation model, submarines are not

smart and actions are uncoordinated. If they see a target they move

towards it to intercept. If it doesn't make an intercept, the submarine

moves to minimize the distance, and hopes the target zigs towards

it. In a coordinated case everyone finds out about a target and

all converge towards the reported position. The ship moves faster

than the submarines and often moves away. Two simple rules emerge:

- If you see the target, move towards it; and..

- If you don't have an intercept solution, do your best to guess.

Brian showed how the simulation augmented his analytical approach.

In estimating probability, each case is run 100 times with coordinated

and uncoordinated submarines. This modeling takes days to run. The

zigzag fitness landscape shows the probability of getting through

for 100 trials. The modeling example shows slow zigs at relatively

long times.

The Admiralty Plans for fast ships, overlaid over the simulation, show that however they came up with the analysis, they did quite well in ending up in the coordinates.

Observations show that zigzagging can help in the case of high

frequency, medium-high angle zigzags, against coordinated submarines.

But can also hurt if reduced to the absurd extreme of low frequency,

high angle zigzag.

Does that mean coordination is bad because zigzagging can defeat it? Zigzagging is more beneficial if the submarines are coordinated, but McCue is loathe to say they should always coordinate. High frequency, high angle zigzagging can reduce the effectiveness of the coordinated submarines to that of the uncoordinated. Today, we still use numbered plans and they may still be the same numbered ones as the original Admiralty Plans.

A question was posed as to whether strategies for the transitor (target) are a mirror opposite the interceptor (searcher).

McCue answered that in modeling the algorithm, the transitor's problem is completely his own and, in fact, very different from the interceptor's.

An interesting note to zigzagging: a target will continue its zigzag

pattern even after it is detected, because it may not know

that it has been found. However, being seen is very less important

than being sunk!

Brian reminded us that Hider Theory is not Stealth Theory. There are many variants of Hider Theory.

“We are not just looking for a target so that we can blow it

up. The challenge is not to just find locational data on the target,

but to find more complete information.”

|