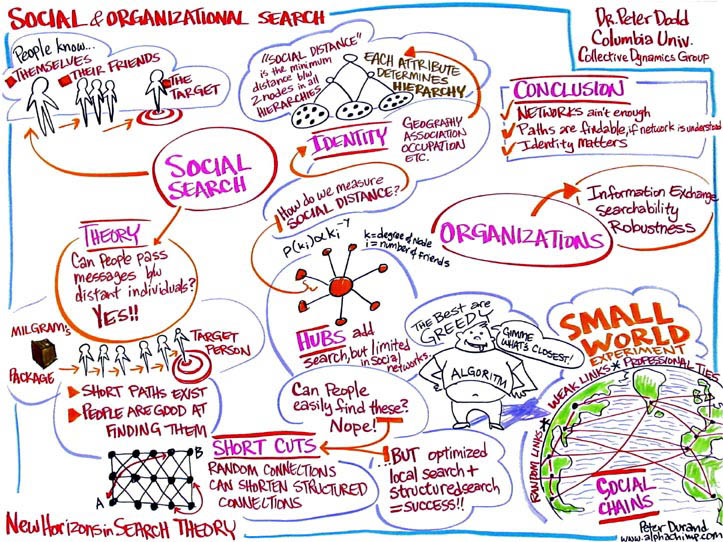

Social

and Organizational Search

Peter

Dodds, Collective Dynamics Group, Columbia University

Tonight

we will talk about Social Search. The

main question with Social Search is, "Can people pass messages between

distant individuals using their existing social connections?" Yes,

apparently because of the "Small World" phenomenon or "Six

Degrees of Seperation".

Click

on image for enlargement

Milgram's

original experiment on this topic was in the 1960's. In his search, he

began with a target person in Boston who was a stock broker. There were

296 senders from Boston to Omaha. In the end, 20% of the senders reached

their target. The results were an average chain of senders that was 6.5.

If

we look at this problem closer, we can see two significant characteristics

of the small world network: short paths and people who are good at finding

the paths. Connected random networks have short average path lengths.

They scale with the size of the system. Social networks are not random.

We need "clustering". In a non-random network there are long

distances (an average of ten steps) between point "a" and "b".

But if we began to add some randomness and regularity to the networks

we can narrow the number of steps in path down to 3.

But

are the short cuts findable and accessible? No. Nodes cannot find each

other quickly with any local search method. How can we navigate? Jon

Kleinberg wanted to look more into navigating a small world network. The

small world network allowed things to vary like local search algorithms

and network structures. He

started to find short cuts by looking at networks and adding local links.

He found that the

'greedy' algorithms work best. The best network you can have is one where

you have long range links that are connecting at different lengths.

Another

type of network is to have hubs that can also search. But hubs in social

networks are limited. Some hubs know a tremendous amount of people for

these searches to work at this level. The hubs begin to create distributed

networks. Hubs

are a contentious issue. They are not absolutely vital when links are

easy to make.

If

we do not have hubs or a latice how do you search efficiently? Which friend

is closer to the target? One solution is to incorporate "identity"

into the experiment. Identify is formed by attributes such as geographic

location, type of employment, religion or recreation. Groups are formed

by people with at least one attribute in common.

Six

propositions about social networks

Proposition

1: Individuals have identities and belong to various groups that

reflect these identities.

Proposition

2:

Individuals break down the world into a heirarchy of categories.

Proposition

3: Individuals are more likely to know each other the closer

they are within a hierarchy.

Proposition

4: Each part of your identity corresponds to the identity hierarchy.

Proposition

5: "Social distance" is the minimum distance between

two nodes in all hierarchies.

Proposition

6: Individuals know the identity of themselves, their friends

and the target. Individuals can estimate the social distance between

friends and the target.

Conclusion

In

conclusion, bare networks are not enough. The

paths are findable if nodes understand how the network is formed. The

importance of identity is very strong.

Applications

With

this knowledge you can improve social network methods, construct peer-to-peer

networks and create searchable information databases.

Recent

Experiment

We

recently ran an experient concurrently that involved 60,000 participants

in 166 countries. There were 18 targets in 13 countries including a professor

at an Ivy League University, an archival inspector in Estonia, a technology

consultant in India, a policeman in Australia, and a veteran in Norwegian

army.

At

each stage, we had 37% participation with a probability of a chain of

length of 10 getting through to the target. 384 chains made it through

which gave us a result of 1.6% of success.

In

the experiment, we found out that motivation, incentive, and perception

matter. If the target seems reachable, the participant is more likely

to participate. For our experiment, we had a median of five to seven.

The complete chains were four.You can compare our results of 5-7 chains

versus Milgram's results of 7-9.

It

is a small world if you think about it. The successful chains disproportionately

used weak ties, professional relationships, and target's work. The chains

disproportionately avoided hubs, friends, and target's locations. In Milgram's

work, he saw that there were key funnels of people who fed information

to the target.

Current

Experiments

We

have two more experiments that we are operating right now. The first one

is Small World Experiment II where you can nominate your own target. The

second is an expert search experiment called the People Finder Project.

|